Klingon language

| Klingon | ||

|---|---|---|

| tlhIngan Hol | ||

| Pronunciation | /ˈt͡ɬɪŋɑn xol/ | |

| Created by | Marc Okrand | |

| — | ||

| Date founded | 1984 | |

| Setting and usage | Star Trek films and television series (TNG, DS9, Voyager, Enterprise) | |

| Total speakers | Unknown. Around 12 fluent speakers in 1996, according to Lawrence Schoen, director of the KLI.[1] | |

| Category (purpose) | constructed languages

|

|

| Writing system | Latin alphabet, Klingon writing systems | |

| constructed languages a priori languages |

||

| Regulated by | Klingon Language Institute | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | None | |

| ISO 639-2 | tlh | |

| ISO 639-3 | tlh | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

The Klingon language (tlhIngan Hol in Klingon) is the constructed language spoken by the fictional Klingons in the Star Trek universe. Deliberately designed by Marc Okrand to be "alien", it has a number of typologically uncommon features. The language's basic sound, along with a few words, was first devised by actor James Doohan ("Scotty") for Star Trek: The Motion Picture. That film marked the first time the language had been heard on screen; in all previous appearances, Klingons spoke in English. Klingon was subsequently developed by Okrand into a full-fledged language.

Klingon is sometimes referred to as Klingonese (most notably in the Star Trek: The Original Series episode "The Trouble With Tribbles", where it was actually pronounced by a Klingon character as /klɪŋɡoni/), but, among the Klingon-speaking community, this is often understood to refer to another Klingon language called Klingonaase that was introduced in John M. Ford's 1988 Star Trek novel The Final Reflection, and appears in other Star Trek novels by Ford. A shorthand version of Klingonaase is called "battle language."

A small number of people, mostly dedicated Star Trek fans or language aficionados, can converse in Klingon. Its vocabulary, heavily centered on Star Trek-Klingon concepts such as spacecraft or warfare, can sometimes make it cumbersome for everyday use — for instance, while there are words for transporter ionizer unit (jolvoy') or bridge (of a ship) (meH), there is currently no word for bridge in the sense of a crossing over water. Nonetheless, mundane conversations are common among skilled speakers.[2]

Contents |

History

Though mentioned in the original Star Trek series episode "The Trouble With Tribbles", Klingon was first used on-screen in Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). For Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984), director Leonard Nimoy and writer-producer Harve Bennett wanted the Klingons to speak a proper language instead of made-up gibberish and so commissioned Okrand to develop the phrases Doohan had come up with into a full language. Okrand enlarged the lexicon and developed grammar around the original dozen words Doohan had created. It would be used intermittently in later movies featuring the original cast: in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier and in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991), where translation difficulties would serve as a plot device.

With the advent of the series Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987)—in which one of the main characters, Worf, was a Klingon—and successors, the language and various cultural aspects for the fictional species were expanded. In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "A Matter of Honor", several members of a Klingon ship's crew speak a language that is not translated for the benefit of the viewer (even Commander Riker, enjoying the benefits of a universal translator, is unable to understand), until one Klingon orders the others to "speak their [i.e., humans'] language."

The use of untranslated Klingon words interspersed with conversation translated into English was commonplace in later seasons of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, when Klingons became a more important part of the series' overall plot arcs.

Worf would later reappear among the regular characters in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1992) and B'Elanna Torres, a Klingon-human hybrid, would be a main character on Star Trek: Voyager (1995). Later, in the pilot episode of the prequel series Star Trek: Enterprise, "Broken Bow" (2001), the Klingon language is described as having "eighty polyguttural dialects constructed on an adaptive syntax"; however, Klingon as described on television is often not entirely congruous with Klingon developed by Okrand.

Language

The Klingon language is studied by hobbyists around the world. Four Klingon translations of works of world literature have been published: ghIlghameS (Gilgamesh), Hamlet (Hamlet), paghmo' tIn mIS (Much Ado About Nothing), and pIn'a' qan paQDI'norgh (Tao Te Ching). The Shakespearian choices were inspired by a remark from High Chancellor Gorkon in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, who said: "You have not experienced Shakespeare, until you have read him in the original Klingon." In the bonus material for the DVD, screenwriter Nicholas Meyer and actor William Shatner both explain that this was an allusion to the "German myth" that Shakespeare was in fact German.

The Klingon Language Institute exists to promote the language.[3]

Paramount Pictures owns a copyright to the official dictionary and other canonical descriptions of the language. Additionally, while the validity is disputed by legal scholars, the copyright of the Klingon language is owned by Paramount as well. While constructed languages ("conlangs") are viewed as creations with copyright protection, natural languages are not protected; only the dictionaries and other works created with them. Mizuki Miyashita and Laura Moll note, "Copyrights on dictionaries are unusual because the entries in the dictionary are not copyrightable as the words themselves are facts, and facts can not be copyrighted. However, the formatting, example sentences, and instructions for dictionary use are created by the author, so they are copyrightable." [4]

Features of the Klingon language were inspired by various real Earth languages studied by Okrand, particularly indigenous languages of the Americas.[5][6] Okrand himself has stated that a design principle of the Klingon language was dissimilarity to existing natural languages in general, and English in particular. He therefore avoided patterns that are typologically common and deliberately chose features that occur relatively infrequently in human languages. This includes above all the highly asymmetric consonant inventory and the basic word order.

In May 2009, Simon & Schuster, in collaboration with Ultralingua Inc., a developer of electronic dictionary applications, announced the release of a suite of electronic Klingon language software for most computer platforms including a dictionary, a phrasebook and an audio learning tool.

Canon

An important concept to spoken and written Klingon is canonicity. Only words and grammatical forms introduced by Marc Okrand are considered proper, canonical Klingon by the KLI and most Klingonists. However, as the growing number of speakers employ different strategies to express themselves, it is often unclear as to what level of neologism is permissible.[7]

Within the fictional universe of Star Trek, Klingon is derived from the original language spoken by the messianic figure Kahless the Unforgettable, who united the Klingon homeworld of Kronos under one empire more than 1500 years ago.[8] Many dialects exist, but the standardized dialect of prestige is almost invariably that of the sitting emperor.

Sources

The following are works which are considered by the Klingon Language Institute to be canon Klingon and are the sources of Klingon vocabulary and grammar for all other works.[9]

- Books

- The Klingon Dictionary (TKD)

- The Klingon Way (TKW)

- Klingon for the Galactic Traveler (KGT)

- Sarek, a novel which includes some tlhIngan Hol

- Federation Travel Guide, a pamphlet from Pocketbooks

- Audio tapes

- Conversational Klingon (CK)

- Power Klingon (PK)

- The Klingon Way (TKW)

- Electronic resources

- The Klingon Language Suite, language learning tools from Ultralingua with Simon & Schuster

- Other sources

- certain articles in HolQeD (the journal of the KLI) (HQ)

- certain Skybox Trading Cards (SKY)

- a Star Trek Bird of Prey poster (BoP)

- Star Trek: Klingon, a CD-ROM game (KCD, also STK)

- on-line and in-person text/speech by Marc Okrand (mostly newsgroup postings)

The letters in parentheses following each item (if any) indicate the acronym by which the source is referred to when quoting canon.

Phonology

Klingon has been developed with a phonology that, while based on human natural languages, is intended to sound alien. When initially developed, Paramount Pictures (owners of the Star Trek franchise) wanted the Klingon language to be guttural and harsh and Okrand wanted it to be unusual, so he selected sounds that combined in ways not generally found in other languages. The effect is mainly achieved by the use of a number of retroflex and uvular consonants in the language's inventory. Klingon has twenty-one consonants and five vowels. Klingon is normally written in a variant of the Latin alphabet (see below). In this orthography, upper and lower case letters are not interchangeable (uppercase letters mostly represent sounds different to those expected by English speakers). In the discussion below, standard Klingon orthography appears in <angle brackets>, and the phonemic transcription in the International Phonetic Alphabet is written between /slashes/.

Consonants

The inventory of consonants in Klingon is spread over a number of places of articulation. In spite of this, the inventory has many gaps: Klingon has no velar plosives, and only one sibilant. Deliberately, this arrangement is quite bizarre by the standards of human languages. The combination of aspirated voiceless alveolar plosive /tʰ/ and voiced retroflex plosive /ɖ/ is particularly unusual, for example. The consonants <D> /ɖ/ and <r> (/r/) can be realized as [ɳ] and [ɹ], respectively. Note that the apostrophe character <'> is not a punctuation mark but a full-fledged letter, representing the glottal stop (/ʔ/).

| Labial | Dental or alveolar | Retroflex | Postalveolar or palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Lateral | ||||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p /pʰ/ | t /tʰ/ | q /qʰ/ | ' /ʔ/ | ||||

| voiced | b /b/ | D /ɖ/ | |||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | tlh /t͡ɬ/ | ch /t͡ʃ/ | Q /q͡χ/ | |||||

| voiced | j /d͡ʒ/ | ||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | S /ʂ/ | H /x/ | ||||||

| voiced | v /v/ | gh /ɣ/ | |||||||

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | ng /ŋ/ | ||||||

| Trill | r /r/ ([ɹ]) |

||||||||

| Approximant | w /w/ | l /l/ | y /j/ | ||||||

Vowels

In contrast to consonants, Klingon's inventory of vowels is simple and similar to many human languages, such as Spanish. There are five vowels spaced evenly around the vowel space, with two back rounded vowels, and two front or near-front unrounded vowels.

The two front vowels, <e> and <I>, represent sounds that are found in English but are more open and lax than a typical English speaker might assume when reading Klingon text written in the Latin alphabet, causing the consonants of a word to be more prominent. This enhances the sense that Klingon is a clipped and harsh-sounding language.

- Vowels

- <a> – /ɑ/ – open back unrounded vowel (in English spa)

- <e> – /ɛ/ – open-mid front unrounded vowel (in English bed)

- <I> – /ɪ/ – near-close near-front unrounded vowel (in English bit)

- <o> – /o/ – close-mid back rounded vowel (in French eau)

- <u> – /u/ – close back rounded vowel (in Spanish tu)

Diphthongs can be analyzed phonetically as the combination of the five vowels plus one of the two semivowels /w/ and /j/ (represented by <w> and <y>, respectively). Thus, the combinations <ay>, <ey>, <Iy>, <oy>, <uy>, <aw>, <ew> and <Iw> are possible. There are no words in the Klingon language that contain *<ow> or *<uw>.

Syllable structure

Klingon syllable structure is strict: a syllable must start with a consonant (which includes the glottal stop) followed by one vowel. In prefixes and other rare syllables, this is enough. More commonly, this consonant-vowel pair is followed by one consonant or one of three biconsonantal codas: /-w' -y' -rgh/. Thus, ta "record", tar "poison" and targh "targ" (a type of animal) are all legal syllable forms, but *tarD and *ar are not. Despite this, there is one suffix that takes the shape vowel+consonant: the endearment suffix -oy.

Stress

In verbs, the stressed syllable is usually the verb itself, as opposed to a prefix or any suffixes, except when a suffix ending with <'> is separated from the verb by at least one other suffix, in which case the suffix ending in <'> is also stressed. In addition, stress may shift to a suffix that is meant to be emphasized.

In nouns, the final syllable of the stem (the noun itself, excluding any affixes) is stressed. If any syllables ending in <'> are present, the stress shifts to those syllables.

The stress in other words seems to be variable, but this is not a serious issue because most of these words are only one syllable in length. Still, there are some words which should fall under the rules above, but do not, although using the standard rules would still be acceptable.

Grammar

Klingon is an agglutinative language, using mainly affixes in order to alter the function or meaning of words. Some nouns have inherently plural forms: jengva' "plate" vs. ngop "plates", for instance. In other cases, a suffix is required to denote plurality. Depending on the type of noun (body part, being capable of using language, or neither), the suffix changes. For beings capable of using language, the suffix is -pu' , as in tlhInganpu' , meaning "Klingons", or jaghpu' , meaning "enemies". For body parts, the plural suffix is -Du' , as in qeylIS mInDu' , "the Eyes of Kahless". For items that are neither body parts nor capable of speech, the suffix is -mey, such as in Sarghmey ("sarks") for the Klingon horse or targhmey ("targs") for a Klingon kind of boar.

Klingon nouns take suffixes to indicate grammatical number, three noun classes, two levels of deixis, possession and syntactic function. In all, 29 noun suffixes from five classes may be employed: jupoypu'na'wI'vaD "for my beloved true friends". Speakers are limited to no more than one suffix from each class to be added to a word, and the classes have a specific order of appearance.

Another important suffix is -ngan, as in romuluSngan. It denotes that someone or something is from the first part of the word—in this case, Romulus. In cases like vereng (Ferenginar), the last ng is dropped in favor of the suffix. Gender in Klingon does not indicate sex, as in English, or have an arbitrary assignment, as in Danish or many other languages. It indicates whether a noun refers to a body part, a being capable of using language, or neither of these. In certain cases, however, there is a word part that defines gender. The words puqloD and puqbe' (meaning "son" and "daughter" respectively), when referenced with other words, imply that -loD means "male", where -be' is female (puq- meaning "child").

Verbs in Klingon take a prefix indicating the number and person of the subject and object, plus suffixes from nine ordered classes, plus a special suffix class called rovers. Each of the four known rovers has its own unique rule controlling its position among the suffixes in the verb. Verbs are marked for aspect, certainty, predisposition and volition, dynamic, causative, mood, negation, and honorific, and the Klingon verb has two moods: indicative and imperative.

The most common word order in Klingon is Object Verb Subject, and, in some cases, the word order is the exact reverse of word order in English:

DaH mojaq-mey-vam DI-vuS-nIS-be' 'e' vI-Har now suffix-PL-DEM 1PL.A.3PL.P-limit-need-NEG that 1SG.A.3SG.P-believe "I believe that we do not need to limit these suffixes now."

Note that hyphens are used in the above only to illustrate the use of affixes. Hyphens are not used in Klingon.

An important dimension of Klingon grammar is the reality of the language's ungrammaticality. A notable property of the language is its shortening or compression of communicative declarations. This abbreviating feature encompasses the techniques of Clipped Klingon (tlhIngan Hol poD or, more simply, Hol poD) and Ritualized Speech. Clipped Klingon is especially useful in situations where speed is a decisive factor. Grammar is irrelevant, and sentence parts deemed to be superfluous are dropped. Intentional ungrammaticality is widespread, and it takes many forms. It is exemplified by the practice of pabHa', which Marc Okrand translates as "to misfollow the rules" or "to follow the rules wrongly." [10]

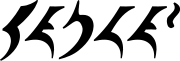

Writing systems

Klingon is often written (transliterated) to the Latin alphabet as used above, but, on the television series, the Klingons use their own alien writing system. In The Klingon Dictionary, this alphabet is named as pIqaD, but no information is given about it. When Klingon symbols are used in Star Trek productions, they are merely decorative graphic elements, designed to emulate real writing and create an appropriate atmosphere. Enthusiasts have settled on pIqaD for this writing system.

The Astra Image Corporation designed the symbols (currently used to "write" Klingon) for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, although these symbols are often incorrectly attributed to Michael Okuda.[11] They based the letters on the Klingon battlecruiser hull markings (three letters) first created by Matt Jefferies and on Tibetan writing because the script has sharp letter forms — used as a testament to the Klingons' love for knives and blades.

Vocabulary

A design principle of the Klingon language is the great degree of lexical-cultural correlation in the vocabulary. For example, there are several words meaning "to fight" or "to clash against", each having a different degree of intensity. There is an abundance of words relating to warfare and weaponry and also a great variety of curses (cursing is considered a fine art in Klingon culture). This helps lend a particular character to the language.

There are also many in-jokes built into the language.[12] For example, the word for "pair" is chang'eng, a reference to the twins Chang and Eng, and the word for "fish" is ghotI'.

Trivia

Mind Performance Hacks mentions learning a constructed language for reasons related to the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis suggesting that knowing an alternate language may provide a different method of critical thought when tackling a difficult problem;[13] the book mentions Klingon as one such language. Other mentioned languages include Lojban and Solresol, as well as a passing reference to Sindarin.[14]

In an episode during season 10 of the comedy series Frasier called "Star Mitzvah", Frasier Crane, played by Kelsey Grammer, gives a speech in Klingon at his son's Bar Mitzvah having been fooled by a Jewish colleague he had let down into thinking it was Hebrew.

In the television series "Chuck," the main character, Chuck Bartowski, and his friend, Bryce Larkin, are both fluent in Klingon, and they use this on two occasions in the episode Chuck Versus the Nemesis.

In the television series "NCIS," in the episode "Witch Hunt, Gibbs, Tony, and McGee, upon entering a Halloween party, looking for a suspect, find the suspect dressed as a Klingon; McGee, who understands Klingon, translates until Gibbs becomes impatient enough to force the suspect to speak in English.

A cryptic message left by a serial killer in Klingon is a plot point in the novel Watch Me by A. J. Holt.

Google offers a Klingon interface

See also

- Alien language

- Klingon culture

- Klingon Language Institute

- Stovokor, a heavy metal band who sing in Klingon

Notes

- ↑ Wired 4.08: Dejpu'bogh Hov rur qablli!*

- ↑ Earthlings: Ugly Bags of Mostly Water, Mostly Water LLC, 2004. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- ↑ Lisa Napoli (October 7, 2004). "Online Diary: tlhIngan maH!". New York Times. http://tech2.nytimes.com/mem/technology/techreview.html?res=9A0CEFD8163BF934A35753C1A9629C8B63&fta=y.

- ↑ NAU.edu

- ↑ There's No Klingon Word for Hello, Slate magazine, May 7, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ An attribution to Okrand may be found in the museum displays at the San Juan Bautista, California State Historic Park, which includes a short mention of the local Mutsun native people whom Okrand studied for his thesis.

- ↑ Klingon as Linguistic Capital, Yens Wahlgren, June 2000. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- ↑ Marc Okrand, Klingon for the Galactic Traveler. Simon & Schuster, 1997.

- ↑ KLI Wiki, Canon sources. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- ↑ Marc Okrand, Klingon for the Galactic Traveler. Simon & Schuster, 1997.

- ↑ Symbols attributed to Okuda: the Klingon Language Institute's Klingon FAQ (edited by d'Armond Speers), question 2.13 by Will Martin (August 18, 1994). Symbols incorrectly attributed to Okuda: KLI founder Lawrence M. Schoen's "On Orthography" (PDF), citing J. Lee's "An Interview with Michael Okuda" in the KLI's journal HolQed 1.1 (March 1992), p. 11. Symbols actually designed by Astra Image Corporation: Michael Everson's Proposal...[3]

- ↑ Puns in the Vocabulary of tlhIngan Hol, Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- ↑ A concept also central to Samuel R. Delany's 1966 science fiction novel Babel-17.

- ↑ Ron Hale-Evans, Mind Performance Hacks: Tips & Tools for Overclocking Your Brain, pp. 199-201. O'Reilly, 2006. ISBN 978-0-596-10153-4.

References

- Bernard Comrie, 1995, "The Paleo-Klingon numeral system". HolQeD 4.4: 6–10.

External links

- Klingon Language Institute

- Klingon and its User: A Sociolinguistic Profile, a sociolinguistics MA thesis

- Klingon as Linguistic Capital: A Sociologic Study of Nineteen Advanced Klingonists (PDF)

- Klingonska Akademien

- Is Klingon an Ohlonean language? A comparison of Mutsun and Klingon

- Omniglot: Klingon Alphabet

- Deutsche-Welle's Klingon Language Service

- BBC article on Deutsche-Welle's Klingon Language Service

- Klingon wikia dictionary in Klingon

- Deutsche Welle Germany's International broadcaster goes Klingon

- Eatoni Ergonomics' Klingon page includes BDF, TTF fonts and a Klingon text entry demo

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||